Two Zero Zero X: Favorite Films of the Decade Pt. 4 — 2003

The Exploding Kinetoscope — 10 Favorite Films of 2003

10. Final Destination 2 (dir. David R. Ellis, scr. J. Mackye Gruber, Eric Bress)

10. Final Destination 2 (dir. David R. Ellis, scr. J. Mackye Gruber, Eric Bress)Hysterical-pitch odium fati sustained over the film's entire running time, Final Destination 2 believes that between death and taxes, you can often dodge your taxes. The adjective — if not meaningful examination of the concept — "nihilistic" is bandied about in pop film criticism, and applied to such inappropriate, diverse guy-movie films as Fight Club, The Dark Knight, the work of Quentin Tarantino and Joel and Ethan Coen. But this practice is not usually coupled with explanation of how and why these films are nihilistic, frequently merely acts as an indicator that the film metes out much destruction and violence, and comes with the unspoken assumption that nihilism is evil, everyone knows this, and everyone agrees. But the Final Destination films, in which "evil" simply does not compute, present a true nihilistic vision, and it is jolly, sadistic and liberating.

In theoretical abstract, the slasher film genre template treats characters as hash marks on a machete handle, a series of deaths standing in line, waiting for their turn to step up to the camera and bite the dust: there shall be six girls for the killer, and when they are used up, the contract is filled. In practice, most slashers are also mystery, suspense or survival stories, and play games with assumptions, toss out red herrings and turnabouts, and make film-long sport of the killer winnowing the herd until a worthy adversary remains. While slasher films are slightly more complex than a checklist of Teens to Kill Today, they still add up to parables about Death Ever Vigilant. Final Destination 2 is not terribly more complex than that checklist. It pushes checklisting to the limit, relishes the slow drag of every downward stroke, completes each mark with triumphant flourish, and, cackling, moves on to the next empty box.

When we take a step back from our lives, loves, problems and relationships, a shape emerges. The pattern: everything dies. Once in awhile, fine, compassionless art comes along that dares to find the whole thing just too goddamned funny.

9. Freddy vs. Jason (dir. Ronny Yu, scr. Damian Shannon, Mark Swift)

9. Freddy vs. Jason (dir. Ronny Yu, scr. Damian Shannon, Mark Swift)It took nearly two decades for the Destroy All Slashers! picture of Fangoria subscribers' dreams to materialize. The prolonged gestation and distance from the films that inspired it serve Freddy vs. Jason well. Maybe it is the waning cultural relevance to audiences and decreasing financial reliance on these ex-titans of idiot terror that facilitates this goony-assed monster cakewalk. Maybe it is the opposite, the canonization of the beasts by a generation who knows the demons by reputation only and by nostalgic old-schoolers — those who recall the humorless, hulking and dumb Friday the 13th films as brutal and compact blunt instruments and the convoluted, dreary Nightmare on Elm Street pictures as witty, and colorful dreamscapes.

Whatever stars had to align for the project to occur, the screenplay is approximately as reverent as a kid wearing a Halloween mask shoving cotton candy through the sweaty, stifling mouthhole. Director Ronny Yu sustains a tone of knowing inanity and fevered all-hero-shots imagery (unforgettable: Jason as a fiery scarecrow cutting a swath through a cornfield party — Jason has it better here than in every Friday the 13th film combined). The raison d'être fight scenes are cleanly, kinetically staged, gag-packed and loaded with lovingly detailed gore. The first, funniest and constant joke of this utterly, happily unnecessary high-concept comedy is that there is a movie called Freddy vs. Jason, because a lot of people wanted to see a movie where Freddy fought Jason.

8. Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (dir. Gore Verbinski, scr. Ted Elliott, Terry Rossio)

8. Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (dir. Gore Verbinski, scr. Ted Elliott, Terry Rossio)If Disney animator and attraction designer Marc Davis once noted that theme park rides are not suited to storytelling (and said with inside authority that “Walt agreed”), then Disney park enthusiasts the world over have been arguing that idea's validity and meaning ever since. Because the most famous rides do tell stories, they are just vague, impressionistic and broad. Or perhaps they don’t tell stories, but utilize a vast grabbag of storytelling technique to give form and lend the impression of narrative to non-narrative experiences. The company as a corporate entity and the creative personnel in its employ have been in continual artistic dialogue about issue since the planning stages of Disneyland, and it is not limited to the treatment and perpetual revision of the parks, but spread across Disney’s media output. Recall, for starters, that the Disneyland television program was born of a partnership with ABC to secure funds for the park’s construction: Disney film and TV and the parks have always been speaking to each other.

The 2000s saw Disney adapting several theme park attractions into feature films, beginning with Mission to Mars (see our 2000 Faves List), and The Country Bears (2002... don’t bother checking the Faves List), and 2003 brought the trend to a climax of sorts with the dumb but fascinating dud The Haunted Mansion and the launch of a series of smart, too-rowdy, wildly popular Pirates films, Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl. Several dark rides, classic and otherwise, play off the Disney movie canon in interesting ways because familiarity with the films implies or causes a narrative throughline. i.e., Snow White’s Scary Adventure, particularly in earliest incarnations, is impossible to “follow” without knowledge of the film. It requires further argument, but some dark rides cherry pick the stories of their parent films, some compress, some allude, some reinvent, but all are in dialogue with another medium.

Film is not necessarily a narrative medium, but it goes without saying that is its most popular application and the vocation of the Disney feature film department. The ‘00s attraction adaptation films then are faced with the task of fleshing out the ride narratives (such as they are), or at the very least inventing personalities and characters to drive those stories (exception?: The Country Bears). The Haunted Mansion, for whatever reasons, is the most steeped in Disneyland lore and chooses a story that approximates the experience of riding the ride, to the point that it visually indicates the path one takes to arrive in New Orleans Square, passing the Enchanted Tiki Room on the way, and turns Eddie Murphy's character and family into surrogate parkgoers trapped in fate's Omnimover. Black Pearl instead takes the simple-but-effective plot of Pirates of the Caribbean — here are the spoils of sin, both earthly treasure and death, and here are the antics that created these skeletons — and runs it forwards, backwards, inside-out. The film crams every nook, cranny, cove and cannon full of Story, elaborating backstory for a zillion evocative but vague details from or coulda-been-from the ride. As the multiple visions of Pirates of the Caribbean talk to each other across the theatre, the movie sweats and strives, expending much effort on those things the ride cannot do. That is: baroquely detailed narrative, the flyaway charm of human performances (Geoffrey Rush and Johnny Depp as dueling opposite-number freakshow captains, one dead, glowering and purposeful, one too-alive, foppish and chaotic, both insane) and — that thing the movies do very best of all — the (erotic) pleasures of moving photographs of pretty girls (Keira Knightly and Orlando Bloom). But the mystery and immersive marvel of the ride elude the movie for the same reasons, resist capture the more the tale is fleshed out, until breathless and exhausting, The Black Pearl tosses one back ashore, drenched, dreamy, and addled.

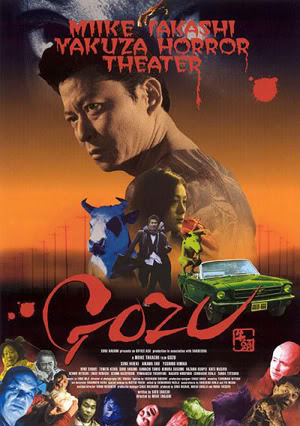

7. Gozu (dir. Takashi Miike, scr. Sakichi Satô)

Like Happiness of the Katakuris and Dead or Alive 2: Birds, Gozu is one of the projects on which Takashi Miike's scatterbrained any/everything-goes inspirations align to form a coherent whole. Gozu rides on the shoulder of gangster Minami, as he is assigned to assassinate his criminal mentor, Ozaki, whose mounting madness is concerning the bosses. Beginning as curveball yakuza thriller and landing somewhere far outside the stadium, the film becomes rapidly infected with Ozaki's madness as it winds deeper through Minami's grey-matter maze.

Other bad-boy/weird-boy artists may share Miike’s delight in gross-out body horror, the love of a dirty joke about sex and/or violence gone too far. But truly no holds are barred here, as homosocial bonding explodes into homosexual panic, the knight’s quest sets down in a labyrinth of sexual confusion, and gods old and new assert their terrifying alien presence. Takashi Miike thirsts for transgression, strives for perversity, cannot resist jerking any string he sees tied to an audience. This keeps his films bubbling and alive, and he knows that in a morass of horror the greatest shock tactic of all are moments of clear, quiet beauty. Miike is fearless.

6. Cowards Bend the Knee (dir. Guy Maddin, scr. Maddin, Adam Gierasch)

Guy Maddin's multipart not-serial "Hands of Dr. Orlac" riff was originally presented in 10 chapter loops, viewed privately through kinetoscopesque peepholes. What an experience that must have been, staring into a tunnel that bends back into your brain, or maybe Guy Maddin's brain. One wonders if Los Angeles is at all envious toward Winnipeg, as it pours hundreds of millions of dollars into productions without a fraction of the inventive results Maddin achieves with a $10 cheque from the National Film Board in pocket.

The armies of screenwriters tasked to invent ludicrous stakes-raising plot points every 20 pages cannot produce events as numerous or outrageous as Maddin jams into sixty seconds, as he hurtles through exposition with terse, exclamatory intertitles. Those all up on Charlie Kaufman's jock for fracturing his commercial impulses into an imagined awful twin brother might die of astonishment as Cowards Bend the Knee follows one "Guy Maddin," hockey star turned hairdresser, who ditches his preggo girlfriend in the middle of an unsanitary abortion, and embarks on a murder quest that his new squeeze will let him touch her boobs, if only with her dead father's transplanted hands. While drenched in/fixated on the techniques of early cinema (and in love with the ironic, mysterious, poetic effect of decay upon the physical materials of formerly-ultra-modern films as much as how cool women's make up was in the '20s), Maddin cuts more times per minute than Michael Bay. Only one of them, however, uses the Moviola's Veg-O-Matic attachment to 1) convey "images" containing "information" and in "a meaningful way", and/or 2) harness the powers of Eisensteinian montage to portray the moral conundrum of fisting your girlfriend's mother to avenge a dead hockey player.

Perhaps direct comparisons are meaningless, but combining apple and orange peels may make nice potpourris.

5. Memories of Murder (dir. Bong Joon-ho, scr. Bong, Kim Kwang-rim, Shim Sung-bo)

From even the first ant-covered corpse found in a drainage pipe, the rain drenched crime scenes are saturated with clues — killings timed to weather patterns, clear and consistent modus operandi, footprints in mud, and a surplus of forensic biological evidence. But alas, it is 1986, in a nation with no labs for DNA testing and no precedent for serial murder. And lo, Detectives Park (Song Kang-ho, more in a moment) and Cho (Kim Roe-ha, obsessed with kicking people) are a bit lazy, a bit sadistic, sloppy of method and utterly unprepared. And so the bumbling, undisciplined rural police force matches wits with South Korea’s first documented serial killer, but the cops are only half-armed. Brooding Detective Seo is sent in from Seoul to assist, and actor Kim Sang-kyung plays him with cool dude quiet, supercompetant with haunted brain always abuzz, and the threatened Park and Cho act as unhelpful Watsons to his stymied Holmes, attempting to show up the better investigator. But Seo is a man unstuck in time, the state of ‘80s forensic science in South Korea can’t keep up. He responds by becoming more haunted.

Memories of Murder, like director Bong’s The Host, approaches its story as if it could belong to a dozen possible genres, allowing blind, unpredictable left-hand turns, sometimes straight into the headlights of oncoming traffic. The strategy illuminates everything in turn. A police procedural about the flouting and botching of procedure, a comedy of errors as nitwits scurry against the tide of horror, a study in masculine one-upmanship and bonding, a crime thriller about ethical slippage as men of nebulous goodness quest to capture an evil made of smoke, a period piece about the way the present leaves scars on the future as history washes away.

In the film’s final moments, Park has long retired from the force, moved on to sunnier pastures, but pays a visit to that ditch from long ago. A passing child indicates that the murderer may have recently stopped by to peer into the tunnel. Song Kang-ho stares into the camera in the greatest close-up of the young millennium. Just his face, straight ahead, expressionless but brimming, as his memory floods: all that has happened, all those intersecting paths, who he’s been, how the case transformed him multiple times over, how these crimes and horrors destroyed him and improved him. A killer walks, a detective looks at a ditch, the afternoon is lovely, the clouds roll insensately on.

One performer’s resume highlights over ten years: Joint Security Area, Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance, The Host, The Show Must Go On, The Good, The Bad and the Weird, Thirst, and more bit part work for Park Chan-wook. Certainly a cool job list, but also of vast range and depth of character. His performance in Memories of Murder alone might have placed him in consideration.

Song Kang-ho is the actor of the decade.

4. Oldboy (dir. Park Chan-wook, scr. Park, Hwang Jo-yun, Lim Chun-hyeong, Lim Joon-hyung, Garon Tsuchiya, based on the comic by Garon Tsuchiya and Nobuaki Minegishi)

Wonder why Oh Dae-su is locked up in that room for 15 years! Wonder why he is released! Wonder what the title means! Oldboy teases with well-measured mysteries and patient reveals. What would you do if you were locked in a room for 15 years? If released? If... And from set-up to final moments, Oldboy offers those great hooky What If?s that fold back to reveal relevant moral questions both less fantastical and more difficult. Live octopus consumption, giant ant hallucination, (and, yes) one-man, one-hammer vs a hallway long goon platoon fight. Oldboy traffics in indelible never-seen-it-before images and heightened situation vitality that is the reason for pulp art.

Oldboy offers among its freaked-out images and wild ideas the most dramatic (multiple senses) transformation (multiple senses) of a leading man of the decade. Choi Mun-sik's soulful and scary performance begins in bloated, drunken aimlessness, melts into shaggy, impotent rage, hardens into dour, inky single-mindedness, shatters into sensitive snowflakes and disappears on the wind.

3. The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (dir. Peter Jackson, scr. Jackson, Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens, based on the novel by J.R.R. Tolkein)

The panoply of geeks and tableaux of mean-anything "yeah, man" symbolism of Jackson's Weta-fied take on Lord of the Rings finally accumulates into an 11-hour version of the 7-minute traffic jam dolly from Week-End across the gatefold art for Eat a Peach. An acid-burned money shot of cave-Lugosi Gollum in ecstasy as he splats into the hot sauce (dude, the camera goes through the Ring) punctuates a climax that boils down to three midgets drawn by destiny into a cartoon volcano to fight over evil jewelry, and well, let us not forget to note that is a very strange way to end a very expensive event movie.

Return of the King is not over after that, and like the Ring, resists dissolving in the heat. How ever exciting or violent or scary Rings was along the way, in any given moment Papa tells us that yes, the fairy tale has a happy ending. And it does. And then tides lap those mythic shores and it just keeps ending. And it just keeps getting sadder. Or... not sad. Wistful. Perhaps Mr. Frodo Baggins does not suffer the torments of poor John Rambo, but like Herman Blume of Rushmore, part of him will forever sigh "Yeah. I was 'in the shit.'" We don't need to look to movie warriors to understand this, or to warriors at all. After you've gone through a life-changing trauma, the thing is, you are changed and traumatized. And that is another way to end a very expensive event movie.

2. The Matrix Reloaded / The Matrix Revolutions (dir., scr. Larry and Andy Wachowski)

"One thing I've learned in all my years, is that nothing ever works out just the way you want it to." —The Oracle, The Matrix Revolutions

By the time The Matrix was released on DVD (and moved 3 million units), it was readily apparent worldwide sensation would be granted a sequel. And while its conclusion is open-ended enough to warrant further installments — in a way, on reflection seems to demand them — the film is actually cannily constructed to stand alone, should the $63 million dollar experiment have failed.

The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions, however, written concurrently, produced back-to-back, released months apart, are the work of storytellers who have been guaranteed a forum. Three chapters, that is the length and breadth of the window. At the conclusion of The Matrix, Thomas Anderson fulfilled messianic prophecy, was resurrected from death to combat the apparent devil of Agent Smith, and flew away as a rabble-rousing Marxist Superman Christ, and it appeared that the Wachowski brothers had gorged heartily on DC comics, anime, Hong Kong action movies and non-medicinal marijuana before stumbling into their Intro to World Philosophy class; The Matrix is psych-pop riot on scale with Jack Kirby's Forth World comics or The Dark Tower. And these things are going on, to be sure, but if The Matrix made it apparent that the Brothers had read Joseph Campbell on the Monomyth, Reloaded implies that the enemy Machines had read Campbell, too.

It is a frequent complaint but not really true that since action scenes in the Matrix itself are the conflicts of avatars in a computer program, those fisticuffs, chases and gun battles are rendered dramatically weightless by the same masterstroke (I know it is frequent, because I've checked Rotten Tomatoes). Certainly by the story's explicit rules, if you die in the Matrix, you die in your chair on the hovercraft thing. Something else is going on with the digital dreamworld though, and it always hinged on the idea that what happens in the Matrix is just as immediate and vital as events in the physical world: there is no spoon, but you have to deal with the idea of the spoon anyway. The Matrix, as literal a reality for the film viewer as Zion, Machine City, the Construct, the Train Station, or any movie you've ever seen, provides, if not complete Brechtian distance, a certain metaphorical brain-padding.

The Matrix Reloaded, point by point, loosens the screws on everything The Matrix seemed to be saying, vis-à-vis Christ figures, Chosen Ones and designated hero-saviors, then in final spectacular blow-out kicks them over. The Matrix does trace Neo's walk down a well-trod path, even if in comparison to Establishment-approved heroes, his route is richer, more subversive, disobedient and slightly bonkers. Those who find the story satisfactory as the Übermensch ascends and the credits roll may gaze upon Reloaded and mutter, as does poor Morpheus, "I have dreamed a dream and now that dream is gone from me."

Maybe we hate to see this happen to Morpheus, who we once met as particularly charismatic kung-fu Ben Kenobi, but there was always a problem with his worldview. Morpheus began his exposition on the Matrix not by emphasizing the horror of bodily imprisonment or painting the human/Machine paradigm as host/parasite, but in terms of ideological oppression. He says the Matrix is a prison for the mind, and frames it in sociopolitical terms, telling Neo that you are enslaved by economic systems, government, media... and religion. He spends Reloaded taking contrary position to rational, pragmatic pessimist Commander Lock. He places faith in prophecy and believes the Oracle to have supernatural powers. He's dogmatic. He is great at criticizing other people's dogma, but blind to his own. For a man who sees providence everywhere, he's somehow never examined the question that begs: providence in service of what?

And Neo breaks it to him, that the very concept of The One, the seductive story of a supernatural savior was another level of control. Neo is dejected too, though it should have always occurred to this man who does not like the feeling that he does not control his life. Well. Nothing ever works out just the way you want it to.

Confidence, vision and purpose bind the Wachowski's filmmaking. Every action sequence is a little carnival of invention, telescoping in scale, packing in oddball poetic detail, always expressed in crystallized, striking images of comics panel clarity, always concerned about — always about — movement in time and space. As every moment is meticulously designed and crammed to the hilt with Meaning and Cool, one is hard pressed to choose a favorite. But if this is about choice, consider this contender, as dark messiah defector Agent Smith steps onto a green-tinted, abandoned urban playground, a viral Loki in black Secret Service suit, a flock of crows dispersing in honey-thick slow motion. Perceptive time snaps back to normal, and Smith gives Mr. Anderson a rousing, ominous speech about his doomsday perspective on "purpose": "We're not here because we're free, we're here because we're not free." And Agent Smith, it turns out, is in no way "wrong." There is a visual motif in the trilogy, of halls full of pillars, which are pummeled by gunfire, chipped away by kicking and punching, used as shields and cover for ambush. The pillars are blasted, but not to be taken for granted.

As the second film variously negates, inverts, complicates and deconstructs the first, so the third reconfigures, reprograms and reinserts the code. The thing about Christ figures is that they don't kick people to death, and must understand perfect sacrifice. The Matrix Trilogy completed is larger than a headtrip cyberpunk messiah myth; it is an exegesis and meditation on the purpose, use, abuse, and meaning of the Monomyth in our lives. Everything that has an end also has a beginning, and this story was never complete until the God From the Machine murmurs, "it is done." Each step of the way, the Matrix films grow increasingly wise, profound and/or profoundly bananas. If all the Wachowskis will reveal is that The Matrix is "about robots vs. kung fu", by the end they are also about mecha vs. tentacle monsters, samurai vs. ghosts, and a giant talking baby head vs. a blind wizard. The final fistfight is as much about Hegelian dialectics as dueling imbalanced Christs, Vishnu avatars amok, the will to power and the strength to sacrifice, control and receptivity, as it is about every slacker's battle with his boss. It's truly the Dude vs. The Man. It's purpose that binds them.

Some things in this world change, some never change, and nothing ever works out just the way you want it to. Maybe that's for the best. The Wachowskis make strong, sometimes difficult, often weird choices with the Matrix trilogy. Now you have to understand why they made them.

1. Kill Bill (Vol.1) (dir., scr. Quentin Tarantino)

A’right, here’s a thing we should get out of the way right up front, you and I. I'm going to say this part in English so you know how serious I am. Kill Bill is one movie. It was written as one movie, and shot as one movie, and treated up to a point in the editing process as one movie. It is one long movie delivered in two parts, just exactly like Children of Paradise. And just-exactly-like-Children-of-Paradise, it is acceptable to spread a viewing across two evenings, but the story isn’t over until the credits roll on Vol. 2.

And now we have that out of the way. So the reason the break between Vol.s is ingenious is that it ought to help underline the complex structure of Kill Bill. The plot worms and winds through the Bride’s list of Things To Do Today: Kill Everyone, but the narrative folds on itself. Not chronologically as in Pulp Fiction's loop-the-loop, but it thematically doubles, a technique Tarantino would explore in the persistent halving of Death Proof and the caduceusian build of Inglourious Basterds, twin snakes winding around a central pole. It is not perfectly accurate that Vol. 1 is all action, ass-kick and adrenaline, Vol. 2 all talk, heartbreak and tears. There is, after all, a lot of jump kicks and a lot of talking in both halves.

If Hamlet is about a protracted case of deciding to do some revenging, exacerbated by a too-smart/crazy-for-his-own-good hero, aware of the impending complications of others' agendas and moral skew, Kill Bill Vol. 1 is about the difficult task of orchestrating and focusing on a hearty revenge even once that choice is made. Also, oops, there are complications. Conventional wisdom has it that Kill Bill is painted broad-stroke bold, a story so primal and simple that it dares to put the ending in the title. Reality is that revenge is never a straight line, and this thing is pitching screwballs before it gets to the mound. Rococo characterization of every supervillain badass, every brutal, balletic action sequence paced and beat-out with a storyteller's instinct, every scene lovingly hand-injected with endorphins, liquefied condensed film stock and bubbling fizzy love. Every prop is a personalized emblem (quickcheck the lioness motif through the films) starting with The Bride's sword, though not every object is gifted with half an hour of elaborated backstory, one has been imagined, from the Pussy Wagon's keychain to Sheriff McGraw's collection of aviator sunglasses, from GoGo Yubari's beaded knife sheath to The Bride's yellow ASICs with FUCK U embossed on the soles. In a world of Red Apples and Fruit Brute, every watch is The Gold Watch to somebody.

And everybody broke somebody's heart, and, revenge being a forest, everyone's trees are blocking someone's sun. They all came from somewhere, are going somewhere, and meet a crisis point in that forest. So here is the Deadly Viper Assassination Squad (even our spelling bee flunkout auteur must know this does not acronymize into "DiVAS"), once bound as teammates, bound in a Massacre at Two Pines, now bound on a List. To varying degrees we see (or will see) where they've been, how they grew, how they changed by choice or circumstance, learn their designated Tragic Flaws and understand their sins. They'll get to change one more time, and then they'll get chopped up, but everyone will have their say. The enigma among these vipers is the silly Caucasian girl who likes to play with samurai swords, the one we've been calling The Bride, 'cause of the dress. The others, it seems, have been schooled and tested, risen and fallen, and have discovered what kind of people they are and will be. The Bride, though, has a long way to go on this mission of self-discovery. Poor girl thinks she's on a revenge mission. We'll see how long that lasts. Silly rabbit, doesn't she know Trix are for kids?

Who knows what kind of life experiences outside "the video store" that Top Critics agree Mr. Tarantino has not had, wish he would experience and bring to bear on his storytelling. From here, it looks like he's lived as much life as any of us.