Two Zero Zero X: Favorite Films of the Decade Pt. 1 — 2000

Preamble

The end of a decade comes but once every ten years! Arbitrary and traditional as Top Ten lists are, the division of history’s ebb and flow into ten-year cycles is even more pervasive and less meaningful. What we collectively imagine as The Sixties or The Eighties are no such thing. History does not wait for round numbers. Nonetheless, here we are. 2000 through 2009.

Historians form a master narrative through an ideological lens. The most persistent shape for film history narratives is a teleological model explaining how film art and film culture has arrived at its present state. When Roger Ebert laments of Transformers 2 that it marks the “end of an era,” he envisions film history piling up to the circumstances where Transformers 2 is possible, a series of manipulations and accidents that add up in backward view to explain how we got to this moment. First the highway is built, then the cars are set in motion, somebody doesn’t brake fast enough, and the dominoes topple until the ambulances arrive. This construction is intended to locate root causes and pivotal events, and also cooks up an aroma of inevitability. Most of us build casual causal arguments about film culture in this fashion, even if we know it involves cynicism or naïveté, simplification and received wisdom.

Consider a familiar case: the present-day event picture. They do exist, and without even bothering with a specific title, imagine a summer release action-fantasy, calibrated for maximum width of appeal and depth of box office receipts, and oiled up with cutting edge technology. One or two of these pictures, though extraordinarily expensive, prop up a studio’s entire fiscal year. Consider how frequently one is presented with the idea that this is the legacy of Star Wars, that lavish effects extravaganzas, shopworn goodie/baddie conflict and juvenile exuberance makes the most money. If we are expressing a bellyache, this is framed as: this is Star Wars' fault. Shade that outline, detail it, change the resolution, whatever. Maybe we want to say it was the one-two punch of Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977) that dumbed down studio product into a stream of mass-appeal blockbusters. Maybe we want to make it a flurry of increasingly powerful jabs with The Godfather (1972), The Exorcist (1975), Jaws and Star Wars, the Coppola film additionally accounting for the contemporary model of awards-bait prestige title epics, the Friedkin for the sure-bet adaptation of any national bestseller, no matter how trashy. Maybe we want to point out that the Movie Brats once celebrated as artistic insurgents during the death throes of the studio system proper ended up establishing the template for the modern blockbuster-as-genre. Maybe we want to complain that things used to be better or different... or that they are roughly the same, that Gone With the Wind was 1939, and The Sound of Music was 1965, or that the meaningful difference is the breaking of block booking and studio production... the pivotal event being the outcome of the Paramount antitrust case in 1948.

Maybe we want to fawn over Casablanca (1942) as the finest example of the studio system’s ability to produce magically slick, universally beloved entertainment. Maybe we want to remember that our greatest film critic, Mr. Manny Farber, thought it was a corny junkyard of spare parts that worked better in other movies. Could be that the demise of RKO is ultimately as responsible for Revenge of the Fallen as anything else.

Each citizen in a world of moviegoers builds a little history of film for themselves, complete with private pantheons, household classics, the unjustly dismissed, overpraised or overlooked. These histories are influenced by our selective blind spots, parents and gurus, taste economies, social engineering and pure dumb chance. List-making is an act of criticism all by itself. It winnows and excludes, reveals and conceals, and for the list-maker causes at least cursory examination of critical values and assumptions.

It is not the most insightful critical practice. List-making is also rife with problems and begs a lot of questions, particularly of the apple/orange variety, and can easily slip into attempt to stratify and quantify the unquantifiable. As much as an awards show, the building of lists can transform art appreciation into a sporting event. When it comes to matters of “Greatest” and “Best,” what we’re really talking about is “Favorites” perfumed with false objectivity. We don’t cotton to objectivity at Exploding Kinetoscope. An objective observation on a movie would read something like “the film was projected onto a screen at a rate of 24 frames per second.” Farber also said in interview that the last thing that matters is whether a writer “liked” the movie or not. Point taken to heart, but it is also the inevitable starting point for all that follows, all critical arguments and observations proceed from preference.

In a series of ten lists of ten, Exploding Kinetoscope will present my ten favorite films from each year of the decade, 2000 through 2009, with a brief appreciation of each of the 100 (or so) films. The brave and bold may wish to read “favorite” as “the best,” but I make no concessions but that they are favorites. Were the project to identify the 100 most influential films of the decade, or most revolutionary, zeitgeist-capturing, popular — “important” in some way — films, the titles would be different. A list-maker might even be forced to include Transformers 2.

The only qualities I am making conscious effort to project are honesty and a degree of eclecticism. The lists were not built with an eye to looking smart, sophisticated, worldly, populist or contrarian. If they end up that way, so be it.

The project begins two months before the end of the year because I take forever to write pieces. This will allow the year to actually end before the 2009 list is unveiled to thunderous silence and boredom. I take forever to write pieces because I am lazy.

HOW THIS WORKS: Practical Matters (AKA – Boring. Skip.)

Like any responsible blogger, I normally contribute an annual favorite films list at the end of each calendar year. The films considered for inclusion in those lists are any new releases first available for viewing in my geographical area during the year in question. As I am located in Los Angeles, this allows inclusion of limited releases — generally for small films, dumped films, and those special December films funneled in for awards season consideration before wide release. It also includes pictures from exotic foreign lands on their first American release.

When I make lists for years gone by, foreign films slip back into proper alignment by their release date in country of origin. If this sounds arbitrary, it sort of is. The reasoning is that year-end lists are built with the intention of pointing readers to recent releases and celebrating personal viewing experience of that year; the purpose of retrospective lists is to weigh recent history after some cooling-off time. So, for example, Sympathy for Lady Vengeance appeared on my original 2006 Favorites list, but now has to contend with 2005 releases — which actually improves its ranking. As to whether festival screenings, non-US limited releases, etc. influence the determination of year of release, I confess the entire system is built on whim and fancy. I have tried to iron out major defects with cursory Internet-based “research,” but feel free to notify the manager of any errors.

Speaking of cooling off, heating up, the dispassionate eye and the seduction of novelty... well, that’s why I am doing this. Things look different in the long view, and I’m more confident in the lists from 2000 to around 2006 than recent years, simply because I’ve had time to see more of 2000’s films than 2008’s, and more time to think about them.

Documentaries, experimental film, art video and genres not yet named all compete for space with narrative features. Features are defined by Academy rules — 40 minutes minimum — and do not vie for position against short subjects... except in one(?) rare (arbitrary) case below, in which a short was just too goddamned good.

Do keep in mind that the completed set of ten lists would not necessarily represent a set of top 100 favorites of the decade. One year’s unranked #13 could be better than another year’s #1. For the bean counters, at the end the individual lists will be shuffled into a weigh-distributed master list of 50 titles.

Favorites of the Two Zero Zeroes, Pt. I — 2000

10. Final Destination (dir. James Wong, scr. Wong, Glen Morgan, Jeffrey Reddick)

10. Final Destination (dir. James Wong, scr. Wong, Glen Morgan, Jeffrey Reddick)Jeffrey Reddick’s repurposed X-Files spec script (that’s fine, it wouldn’t have jibed with what we see in “Tithonus”) was repurposed and rewritten into a feature by Files first stringers Glen Morgan and James Wong. The hook is irresistibly silly, a slasher movie with no slasher, and in a stroke of bold, unapologetic redundancy, “death” itself is the killer. Boring teenager Alex (the boring Devon Sawa) has an unexplained precognitive vision and convinces a handful of passengers not to board a doomed 747. Thus thrown off-track, Death is forced to work overtime to burn, decapitate and smush all escapees. Imagined as an implacable force of nature and visualized as shit falling over and blowing up, Final Destination’s vision of mortality is the most fatalistic in all pop horror cinema. The first great horror franchise of the brink of the new century, the Destinations are loud, rude, pitiless black comedies with one single-minded two-fisted joke to tell.

Director James Wong moves through the hollow space between death setpieces at an acceptable clip. The characters are bound to be little but Reaper-feed, but the first installment doesn’t even bother to sketch its people as types or caricatures (however, everyone is distractingly, pointlessly named after historical horror film figures). Sequels would reach grander heights of invention, comedy and ludicrosity, but Final Destination is the first wicked hammer drop in death’s Rube Goldberg machine. The joke is on everything with a beating heart.

9. Memento (dir. Christopher Nolan, scr. C. Nolan from short story by Jonathan Nolan)

9. Memento (dir. Christopher Nolan, scr. C. Nolan from short story by Jonathan Nolan)Pity poor Leonard (Guy Pearce, looking like a battered, blown-out half-developed Polaroid) who cannot form new memories since his injury, whose brain self-purges approximately every ten minutes and whose body constantly snaps awake while in perilous situations. Pity the audience of all sloppily written and edited pop cinema product, for we possess attention spans, allowing us to track plot holes, oversights and fudge-ups, recognize clichés and retain information without being condescended to. Presupposing capable viewership, Memento runs backwards, requiring that its revenge thriller clockwork not only be tooled with precision but fully reversible. The film’s thrumming ontological malaise and show-off structure tend to overshadow its pleasures as a terse and chewy crime picture, but these concerns are bound up together. As metafiction on the art of narrative filmmaking, Memento reconfigures the steady, regulated information leak of storytelling, applying its full smarts to suspense and mystery genres in which the shielding of the dealer’s cards matters the most.

If Memento says nothing more profound than that reality is simply the state in which we find ourselves second to second, that is enough. Leonard has lost the illusion that he is the sum total of experience, that a life lived provides anything but consequence and circumstance, that history conspired to make him the man he is today. He loses that when his head smashed into a mirror: self-perception shattered, slate wiped, scars permanent. Those who charge forth with confidence that we know who we are, know where we’re going, know where we’ve been labor under a very practical delusion. Those who wonder in anguish over who they are may be asking a question that does not make sense: you are the man looking in the mirror and asking who you are. Memento makes over Camus’ The Stranger as sunbleached California noir, in which perception is slippery, but it is all we have. The pictures lie. You must remember this.

8. O Brother, Where Art Thou? (dir., scr. Joel and Ethan Coen)

8. O Brother, Where Art Thou? (dir., scr. Joel and Ethan Coen)A rangy, meandering tall tale of the Depression era Deep South, Joel and Ethan Coen’s sole musical is also an amiably stoned ramble through screwball comedy, self-serious social issue films, and cornepone rural comedy. After 15 years of Coen films, the temptation is strong as ever to create run-on lists of every genre and text being pastiched, lampooned and paid homage, then marvel that the resultant film does not really resemble any of that parentage.

A swiped Preston Sturges title is applied to the sort of goofy crowd-pleaser that it was meant to stand in contrast to in Sullivan's Travels, and recalls some contradictions that Sturges shares with the Coens. These are, namely, ambivalence about characters, swinging between affection and distain, and incontrovertible authorial smarts playing push-pull with the desire to be taken Seriously. As Sullivan alludes in the broadest ways to Gulliver's Travels, O Brother purports to adapt Homer’s Odyssey. And it does, with cute, unceremonious parallels and offhand references, but the important thing is its purpose and spirit. O Brother is a period piece set not in a real historical era but in the accumulated imagined American past, populated by icons and legends, historical whitewashing and spooky folktales. Like the Odyssey, it is the historical epic romance of a nation as it wants to see itself. In the case of America, that is with much contradiction, truth and wishful thinking. O Brother presents the American hero as scrappy but upright, resourceful but hardscrabble, charming and clever but not too clever, rugged and handsome, wise-ass and silly, wandering but family-obsessed, lazy and hard-working. Above all, the very shape and subject of this comic myth celebrates and satirizes in the American character an incompatible desire to be an impossibly lucky winner and still possess hard-luck simple-value “Authenticity.” Witness, as Ulysses Everett McGill, proud and indignant that he is Bona Fide, makes a big success by recording that timeless ode to American shit luck, “Man of Constant Sorrow”. Adopting the Greek Pantheon sure makes it a lot easier to reconcile that that some days your manifest destiny is to roam, and some days it’s nothing but depression.

7. Mission to Mars (dir. Brian De Palma, scr. Jim Thomas, John Thomas, Graham Yost)

“Drifting through eternity will ruin your whole day.” So goes some wisdom from Brian De Palma’s marvelous spaceman thriller. Mission to Mars is practically a humanist retort to 2001: A Space Odyssey, its climactic moments dedicated to a pretty and inspiring filmstrip on biological evolution on Earth. Containing something to bewilder or sour nearly ever viewer, even the film’s final statement of wonder is marred by one badly designed transitional era CG alien effect. But all De Palma films have a little of this wonder, and no small amount of dread, as starry-eyed humans are ricocheted around a cosmic pool table along networks too daft to make sense of, dragged by forces they cannot see. Mission does, in its finale, marvel at nature, but until then it is variously spooked and awe-struck.

The climax of physical action occurs in the black void, of course, stranded between heaven and earth (well... between spaceship and Mars), safe home and unknown adventure, chilly womb and blazing death. The suspense device is of properly calibrating jet pack thrusters and conserving limited fuel supplies; the moral questions are of the same stuff: applied force, inertia, impossible choice and aiming carefully while navigating through space.

One zero G setpiece alone sees the director pushing the cinematic apparatus’ ability to organize space and time to a new plane: it is a De Palma Future. As the ship is about to enter orbit around Mars, a micrometeorite barrage perforates the hull, one space suit helmet, and one astronaut’s hand: bam, bam, bam, these are the crises in poetic simplicity, tiny rocks hurtling through infinity just to fuck up four heroes. The ensuing repair effort is a suspense scene of elaborate construction without parallel... except in the De Palma canon. Beginning with the image of atomized blood globules swirling lazily about the pristine ship, the sequence expands and flows into airless abstract 3D museum diorama. As four crewmembers undertake separate tasks in different locations and the atmosphere rapidly suctions out of the craft, their work unites the action, a seamless vignette about punctured seams. The source of the first leak is detected via the floating blood droplets, the second by a serendipitous packet of Dr. Pepper. The pieces and particles flocking in one direction to create a whole, the scene snakes through space, inside and outside, perfectly oriented in a place where up and down do not apply and time is the crucial dimension. Linked in purpose, discrete no longer, like the chromosomes sent to a blue planet from a red one, like the astronaut’s DNA model built of M&M’s, like the Dr. Pepper and the blood, like the clouds of Martian dust. Like pictures threaded in sequence, moving in time together to tell a story.

6. Dancer in the Dark (dir., scr. Lars von Trier, songs by Björk)

6. Dancer in the Dark (dir., scr. Lars von Trier, songs by Björk)Old-time women’s picture hokum, nothing in Lars von Trier’s musical extravaganza holds any water or makes any sense, except that melodrama tells its own sort of truth. When the indignities and cruelties upon the innocent are piled high enough, any weeper turns into a dark comedy; tell a horror joke from the inside out, and with enough sincerity and it becomes a tragedy.

This joke is about a girl who gave and gave and a world that took and took, until she had nothing left. Von Trier has told this one before, would tell it again, and the challenge this time around must have been to test the limits of weepy excess while purging every semblance of reality: how far can either fundamental component of the film be pushed before it undoes the other? The martyr heroine is not only impoverished, abused, wrongfully persecuted and slowly going blind, but apparently suffering some intellectual disability, her every interaction and behavior exactly the kind of thing no one would do. Björk plays Selma as a walking Sacred Heart, a lived-in, humanity-stinking performance, a matted waif that one might feel compelled to slap for her own good, if she were not constantly being slapped already. The music is exuberant, aching and achey, and bitterly ironic in context. Björk’s own records thrive on a similar tension, as dance music that cannot be danced to, soaring pop as intimate and uncomfortable as crawling through the singer’s throat. As a victim/collaborator in Von Trier’s campaign, Björk adds another layer of contradiction and mystique to both the film and the art project of her public persona. For in Von Trierland, it is possible to become confused as to what is sincere or put-on, sophisticated or juvenile. Dancer in the Dark is both, of course. The kind of emotional rawness and thoughtful technique on display are simply too much work to muster up for a derisive chuckle. Dancer in the Dark is Passion play as escapist Mamoulian musical, and vice versa.

5. American Psycho (dir. Mary Harron, scr. Harron, Guinevere Turner)

5. American Psycho (dir. Mary Harron, scr. Harron, Guinevere Turner)Brett Easton Ellis’s gasbag novel is punctured, drained and distilled into an elegantly mean and hilarious feminist tract by director Mary Harron and her co-screenwriter Guinevere Turner. While Ellis’s method of literary satire is to stand in one place, bare-knuckled, and punch the same spot over and over and over, Harron and Turner feint and bind, slice and dice with a thin, exacting blade. The subject is manly competition and conspicuous consumption in the world of late-1980s Wall Street investment banking, the case study one Patrick Bateman and the crimes engendered by boundless privilege and ridiculous amounts of money: disconnect from humanity, ennui, failure of taste and serial murder. As a period piece takedown of extreme yuppiedom, American Psycho picks an easy target, but courtesy of Ellis there exists a graceless, hammering take on the same material, proof that this is not as easy as it looks. Whether one finds the ‘80s stage dressing deft and funny or irrelevant nearly a decade after the fact, the thesis is tied to no one time and place, a hysterical burlesque of late period capitalism careening into a barbaric dead-end, the human body made ultimate disposable luxury commodity.

The excesses of Ellis’ novel are the point, but it is more excruciating than funny or horrifying, ideas more interesting to discuss than to read. Harron and Turner’s choice to clean up the grue, besides making the book filmable, eliminate Ellis’ habit of rubbing an audience’s nose in the material. The only lamentable cuts are of Bateman’s most far-out hallucinations — being pursued by a park bench, and witnessing a Cheerio being interviewed on television — that might have strained credulity even with this most unreliable narrator. The psycho himself is alternately locked in a human skin sarcophagus, and on berserk nude chainsaw rampage. While the film is largely lodged inside Bateman’s head, crucial space is made for the voices of the women of American Psycho. Turner is tellingly cast as the only woman who laughs in the protagonist’s face. In a moment like a clear, mournful bell amidst the cacophony, Bateman’s secretary, Jean (Chloë Sevigny, earnest and breakable, good as gold), steals a peek at the boss’ diary, and finds only primitive childish doodles of mutilated women. The film still closes with Ellis’ bleak jabber (and portentous inscription: THIS IS NOT AN EXIT), Bateman’s final embrace of nihilistic abandon, brain-snapped and sweat-drenched. But the summary of Harron’s Psycho is in the eloquent, beautifully composed scene of Jean alone, confronted with the swarming, dehumanizing rage of Bateman’s notebook. Whether the crimes of the book are “real” or not, the disease behind the symptoms is the same, and lost, confused, and hurt, Jean weeps.

Bonus points for a credits sequence that prefigures Dexter's opening by 6 years.

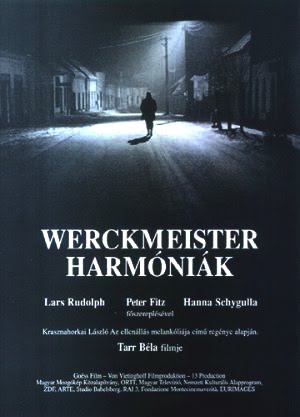

4. Werkmeister Harmonies (dir. Bela Tarr, scr. Tarr, László Krasznahorkai, from the novel The Melancholy of Resistance by Krasznahorkai)

3. In the Mood for Love (dir., scr. Wong Kar-wai)

This is a film about extraordinarily beautiful people smoking cigarettes, which make extraordinarily beautiful smoke, and looking moody, sexy and tragic while they do it.

The story of Chow Mo-wan (Tony Leung) and Su Li-zhen (Maggie Cheung) lovers-never-to-be, neighbors united because their own spouses are cheating on them with each other, is both emotionally complicated, poetically pared-down. It is speaks to many things inside those prone to heartsickness, romantic longing and indolence. Like a series of lugubrious interlocking etudes, In the Mood for Love is vague and elliptical enough, repeats variants on its own themes with such seductive rhythm as to encompass itself in forward and reverse. It is a story about how a mutual case of blue balls prolonged over the better part of a decade, combined with a propensity for melancholy, can cause the afflicted to inflate intimacy and longing into having mistimed meeting one’s one and only Soulmate. In more sympathetic light, the opposite spin: love and connection flit through our lives, prolonging defining moments with an aching sustain, and sex just has nothing to do with romance. Chow and Su torture themselves into increasingly lovely emotional and-or sexual starvation, their stated motives may be to maintain the moral rectitude and dignity that their spouses could not. Of course, this just makes their anguish more perverse, their behavior creepier and more damaged.

Should you remove the mud, and let the whispered secrets float out like scribbled plumes of cigarette smoke, there is every chance that the voice of a broken heart has nothing to say but “Oh my God, oh my God. I should have fucked her.”

In the Mood for Love is truly and deeply about how gorgeous movie stars can look while smoking cigarettes in the rain.

2. “The Heart of the World” (scr., dir. Guy Maddin)

2. “The Heart of the World” (scr., dir. Guy Maddin)“Heart of the World” IS:

-Six minutes and some few seconds long.

-An erotic montage-edited frenzy about the erotic frenzy of montage editing.

-A romantic evocation of the spasmic lovemaking of silent Soviet sci-fi, Fleischer brothers shorts, experimental Marxist documentary and many other sorts of popular entertainments currently in vogue with audiences the world over.

-A loving, meticulous recreation of German Expressionism and Soviet montage that looks precisely like no Expressionism or montage that ever existed.

-Absurdist redemptive melodrama about the redemption of melodrama!

-A full history of passion, love, death, resurrection, erection, economics, religion, science, sacrifice and birth conveyed in such bold, decisive strokes that it takes place entirely in hyperspace!

-KINO KINO KINO KINO!

1. Battle Royale (dir. Kinji Fukasaku, scr. Kenta Fukasaku, from the novel by Koushun Takami)

1. Battle Royale (dir. Kinji Fukasaku, scr. Kenta Fukasaku, from the novel by Koushun Takami)Directed by the 70-year-old Fukasku, the last great film of the millennium closes with an imperative to the young: RUN.

Japan of the undefined near future finds its economy collapsed, unemployment rates soaring and youth in rebellion. The implied fascist government instates the Battle Royale program: each year, a ninth grade class is abducted, shipped to a small island, and made to participate by slaughtering each other until one child remains standing. From this high concept, equal parts compelling and appalling, proceeds Battle Royale. The giggly, angry, black satire plot reads, on paper anyway, like a premise John Waters might have imagined, had he been born some thirty years later. Its barely-science-fiction kill-or-be-killed tale meditates on universalist themes common to Lord of the Flies, The Most Dangerous Game, and Stephen King from Roadwork to Under the Dome: the scary speed with which the body’s survival instinct kicks in when under duress, the fascinating and varied ways in which civility disintegrates and societies break down.

Battle Royale is bitterly funny to be sure; its political bite sinks deep into the luxury culture, unhealed generation gap and entertainment tastes of postwar Japan, teeth scraping bone. The premise alone is enough, an overstated, ferocious lampoon of conservative social politics, and their bad ends for the defenseless and innocent. The BR program is ostensibly created to quell the rising tide of youth discontent, but is motivated by adult failure, fear, and anger scapegoated onto the nation’s teens.

But Battle Royale does not play out as a bad taste splatterpunk comedy, a sadistic action movie or, really, in any way expected at all. The film’s main modes inside its pointed, complicated satire are rich, novelistic storytelling and quiet, sensitive poetry. The strong backbone allows Fukasku to check in with the 42 students in various combinations all over the island, and on their mysterious teacher Kitano (Takeshi Kitano, also malevolent and weary), in quick sketch intertwining vignettes. Comically blunt intertitles punctuate the deaths, but the survival game is not the heart of this story, and the rest unfolds in the oblique, haunted tone of flipping through a high school yearbook with a headfull of psilocybin.

In careful, spare strokes, the film marks out miniature portraits of its dozens of 15-year-olds. The emotionally intense reality of adolescence is so vivid that Battle Royale seems willed into existence by the resentments, heartache and irrational impulses of the ninth grade class. Still, somehow the film stands at a contemplative distance from this hormonal miasma, those love stories that are really crush stories, bullying that is really dismemberment. The abject nastiness, adorable naïveté and poignancy of teenage social interaction is observed with empathy — respect, even— and on their own terms.

In the greatest movie scene of 2000, fierce and beautiful class track star Chigusa (Chiaki Kuriyama, blood type: A) is dying. Her friend Hiroki (Sousuke Takaoka) finds her, and though freaked out, picks up the dying girl and sits with her as dusk falls. And what can she want in those final moments? What is important right then? She asks Hiroki if he is in love. And yes, he is. She asks: but not with me, right? And no, not her. Hiroki can barely stand to look. But he will stay with her. Still nervous, even with nothing to lose, Chigusa musters everything she has and... tells Hiroki that he looks cool. Hiroki gives his friend the most beautiful last moment possible, as her heart simultaneously breaks and slows and stops. He tells her: “You’re the coolest girl in the world.”

What does it mean, then, to tell a generation to “RUN”? Contemporary as its other concerns may be, Battle Royale is not an anthropological exposé on the slang, savagery and mating habits of modern Japanese youth. It is about what it is always like to be 15, what it has always been like to be 15, and what 15-years-old means to a 70-year-old man. There is nothing sweeter than catching the extremely jaded in a moment of wistful reverie.